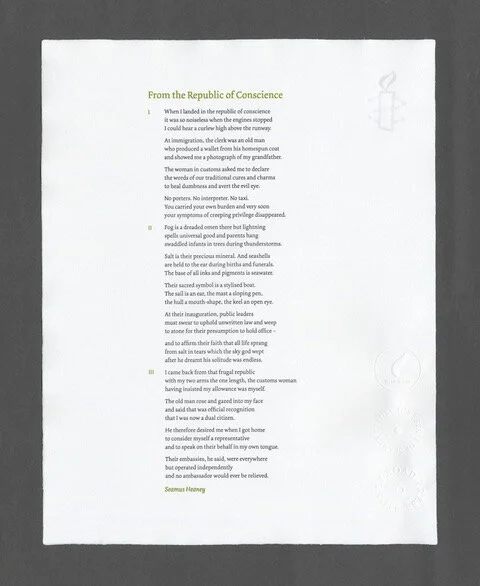

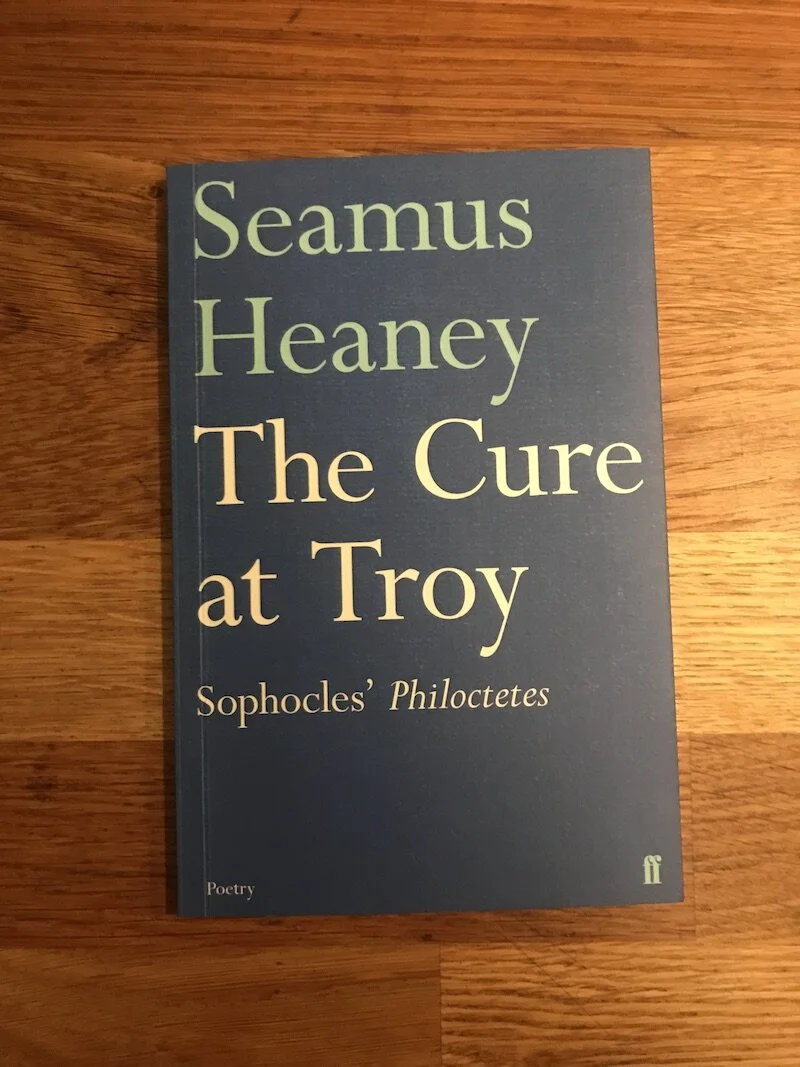

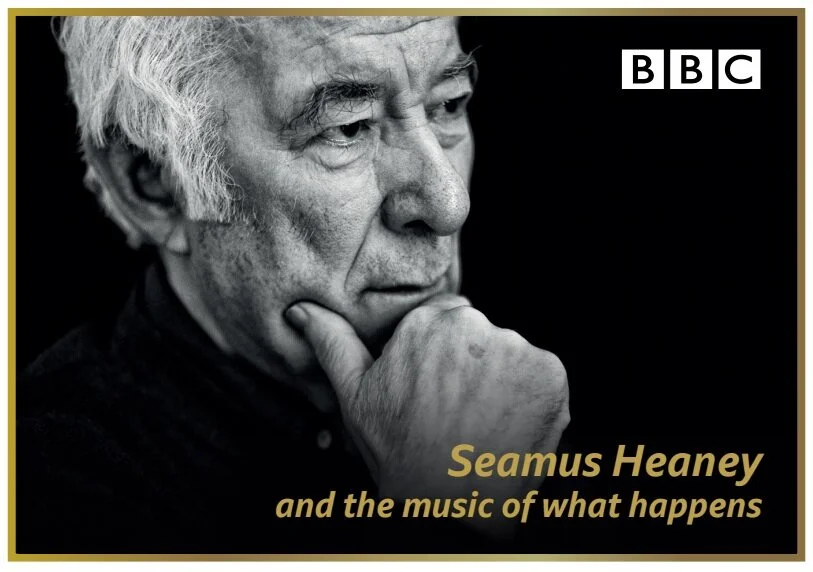

Forty years after its first publication in 1979, Seamus Heaney’s fifth collection Field Work is considered afresh by Bernard O’Donoghue

As a heading to the chapter on Field Work in Stepping Stones, his 2008 book of interviews with Seamus Heaney, Dennis O’Driscoll uses the phrase ‘The life we’re shown’ from the poem ‘The Badgers’:

How perilous is it to choose

Not to love the life we’re shown?

It is a fitting indication of the shift that Heaney says he wants to make, away from the constrictions and public obligations lamented in ‘Exposure’ at the end of his previous volume North towards a more literal representation of the life he is shown after the family’s move from Belfast to the countryside in Wicklow. He ‘no longer wanted a door into the dark, but a door into the light’; he wanted to be able to use the first person to refer to himself and his own experience again, rather than to be a spokesman for community.

This personal aspiration is apparently confirmed by the new volume’s pastoral title Field Work. And its opening poem ‘Oysters’ seems to assert a wish for an indulgent artistic freedom that could ignore responsibility for the public world. The poem expresses an ‘angry’ resentment that the speaker’s ‘trust could not repose/ In the clear light, like poetry or freedom’, and it ends with eating, not as an indulgence, but as an aggressive action that links back to the violence of the earlier verbs describing the oysters: ‘ripped and shucked and scattered’. Like so many of Heaney’s poems, it answers its own challenge.

‘Oysters’ sets up wonderfully the ambivalence of this profound book, as its artful title does too. Field Work, does not in fact mean work in the fields when you think about it; it means the preparatory research work for some kind of pronouncement. Rand Brandes, Heaney’s bibliographer, reports the earlier titles that had been considered for this conciliatory book: ‘Polder’, a Dutch-derived word for a patch of land surrounded by water, rejected at least in part because of uncertainty about its pronunciation, but also perhaps for its narrowness of application; and ‘Easter Water’, rejected because of its undue positiveness. Field Work, with its rural-sounding title (a bit like the later District and Circle which similarly has an implication of locality which is no more than skin-deep) is the perfect title for a book which will take as its material ‘the life we’re shown’ but draw diverse morals from it.

After all, if this post-North book is no more than a determined move towards the fields as a retreat, it is very surprising that it contains two of Heaney’s finest and most anguished elegies set in The Northern Troubles, ‘The Strand at Lough Beg’ about the killing of his poet’s second cousin Colum McCartney, and ‘Casualty’ about the death in a bombing of his friend, the fisherman Louis O’Neill. Furthermore, one of the early poems in the book ‘After a Killing’ extends the violence to Wicklow, the new retreat, with the killing of the British Ambassador there.

Of course there is also a strongly lyrical and celebratory aspect to Field Work – in the ‘Glanmore Sonnets’, for example, notably in the third poem (originally the sonnet that the sequence began with):

This evening the cuckoo and the corncrake

(So much, too much) consorted at twilight.

It was all crepuscular and iambic.

Metrical regularity is linked to the rural lyricism of the setting. Similarly, Heaney says the stanza form was ‘what made the whole poem’ in the case of ‘The Harvest Bow’. But writing in an accomplished form in the first person about direct experience of the life we’re shown does not mean that negative aspects of that life can be ignored. The volume ends with one of the most horrific scenes of violent hostility in all Heaney’s poetry, the story of Ugolino from Dante’s Inferno. But between the nerve-jangling clacking of oyster-shells at the start and the horrific gnawing on the ‘victim’s ravaged skull’ in ‘Ugolino’ come the major elegies, the erotics of ‘The Otter’ and ‘The Skunk’, and the idyllic exultation of the sonnets. ‘Up to North, that was one book’, Heaney said. But the new departure that followed that book in Field Work was by no means in a single direction. It is far from his longest book; but it is arguably the book which is powerful in the greatest variety of forms, subjects and emotions.

Bernard O’Donoghue is a poet and Emeritus Fellow of Wadham College, Oxford. He is currently at work editing Seamus Heaney’s Collected Poems. His most recent collection is The Seasons of Cullen Church (Faber).

For more information on Field Work, click here.