Exactly thirty years ago, in April 1988, Seamus Heaney delivered the inaugural Richard Ellmann Lectures at Emory University in Atlanta. Here, Professor Ronald Schuchard – Heaney's close friend and the founder of the lecture series – remembers a joyous occasion and an ongoing legacy.

Richard Ellmann, the Goldsmith’s Professor at Oxford and eminent scholar of Joyce, Yeats, and Wilde, had been coming to Emory University for an annual five-week, short-course visit since 1977. When in 1979 Emory received a munificent gift of $105 million from Robert W. Woodruff, CEO of Coca-Cola, Ellmann was here to encourage President James T. Laney to devote some of the windfall to creating a research library within the Woodruff Library. In 1979 Emory did not have any research collections in modern literature, until Laney sent Ellmann to a Sotheby’s auction to acquire from Lady Gregory’s Coole Park library most of her unique collection of books and manuscripts by W. B. Yeats, thereby setting in place the cornerstone of what became the Manuscript, Rare Book, and Archives Library (MARBL), now the Stuart A. Rose Library. Ellmann continued to advise on acquisitions, and he was here on 9 March 1981 to welcome Seamus for his first reading at Emory and to show him some of the extraordinary Yeats items from Coole Park. At a party afterwards they were treated to some sips of the finest South Carolina moonshine (Heaney thought it a rival to Irish poitín) to seal their southern bonds.

In the fall of 1986, we learned that Ellmann, who had placed his own Yeats collection at Emory, was dying of Lou Gehrig’s disease (ALS). In February 1987, three months before Ellmann’s death in May, President Laney flew to Oxford to tell him at bedside that Emory was establishing the Richard Ellmann Lectures in Modern Literature in his name to perpetuate the legacy of his public lectures, his clarity and elegance in speaking about serious literature to general audiences. And when he asked Ellmann whom he wanted to inaugurate them, he replied at once, softly, ‘Seamus’. And so Seamus and Marie arrived in April 1988 for the inaugural Ellmann Lectures, ‘The Place of Writing’. ‘I was sensible of the high regard implicit in the invitation,’ he wrote in his ‘Author’s Note’ for the published volume,

but daunted also by its high demands, since the Richard Ellmann Lectures in Modern Literature would be measured against the standards of excellence that he represented. Nevertheless, the fact that Dick had assented to my being asked . . . emboldened me to accept. . . . Everyone who assembled for the occasion seemed to do so with a specific personal commitment; one had a feeling that the immense, equable force of Ellmann’s personality, scholarship and teaching was being celebrated in a deliberate and truly ceremonial way. At the formal hospitalities surrounding the inauguration of the series, at the informal but no less hospitable gatherings that ended each day, and on the occasions of the lectures themselves, there was a constantly renewed awareness that we had come together because we cherished a man of irreplaceable worth. Underlying the rightly public aspect of the events, there was an unusual prevailing mood of tenderness and loss.’

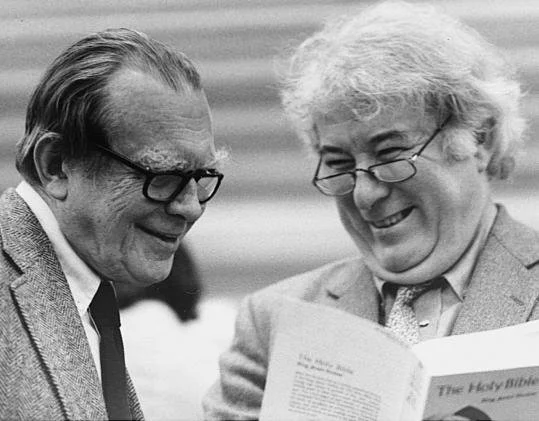

Seamus’s lectures and reading of poems coincided with his forty-ninth birthday on 13 April 1988, all held in Glenn Memorial auditorium before full-house audiences of 1200. The opening lecture was appropriately titled ‘The Place of Writing: W. B. Yeats and Thoor Ballylee’; the second, ‘The Pre-Natal Mountain: Vision and Irony in Recent Irish Poetry’, focused on Muldoon, Mahon, Longley and MacNeice; the third, ‘Cornucopia and Empty Shell: Variations on a Theme from Ellmann’, brought in the works and places of Kavanagh, Kinsella, Montague, Friel, and Beckett. The three lectures were published as The Place of Writing (Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1989), with a frontispiece and endpiece of Heaney and Ellmann walking together on the Hill of Howth in the summer of 1982.

Seamus Heaney's Ellman Lectures were collected in The Place of Writing.

Richard Ellmann and Seamus Heaney, from frontispiece.

On the informal side, there were indeed festive events, beginning with a pig roast, enhanced by a three-tier, multi-jet margarita fountain and a five-piece mariachi band. Seamus immersed himself in the spirit of it all, finding somewhere a T-shirt emblazoned with an armadillo, an Arkansas Razorback hogshead headpiece, and an expanding, accordion-like manuscript book, which he titled ‘A Horn Book of Ye Hog Days’, hastily filled with poetry for the occasion. A clandestine journalist was present to record the scene, and to print prominently in the Atlanta newspaper next day a large photo of Seamus reading in his low-country regalia:

With a Georgia pig freshly hoisted from the barbecue pit, one of the great bards of Ireland was going whole hog. Nobel committee take note. Seamus Heaney, that white-haired, rosy cheeked lamp of genius in the well-packed Armadillo T-shirt, had written another poem that he would now recite. As soon, that is, as he could set his margarita down and amble to center stage, or at least the center of a backyard deck. Once there, planted as firmly as though on his native sod, he inhaled, then intoned, thumping out the rhythmic syllables:

Ell-mann Lec-tur-ers be-ware!

Before you venture South, prepare!

Scorn the way that Heaney did it ‒

Writing desperately at midnight,

Like a scribe on overtime,

Counting beats and pointing rhyme.

And to the delight of a chorus of well-wishers gathered for his 49th birthday, the brilliant Poet of the Bogs was off on a rousing rendition of freshly minted doggerel that included a reference to himself ‘being treated like a hero / As blue grass fiddlers bow like Nero, / Bending elbows, quaffing toasts / To compound, dear, familiar ghosts.’

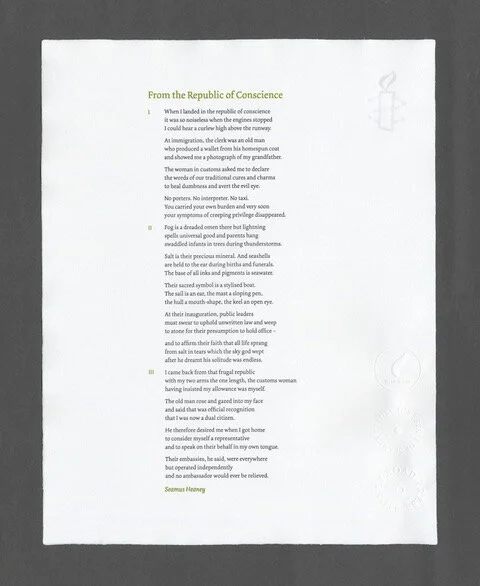

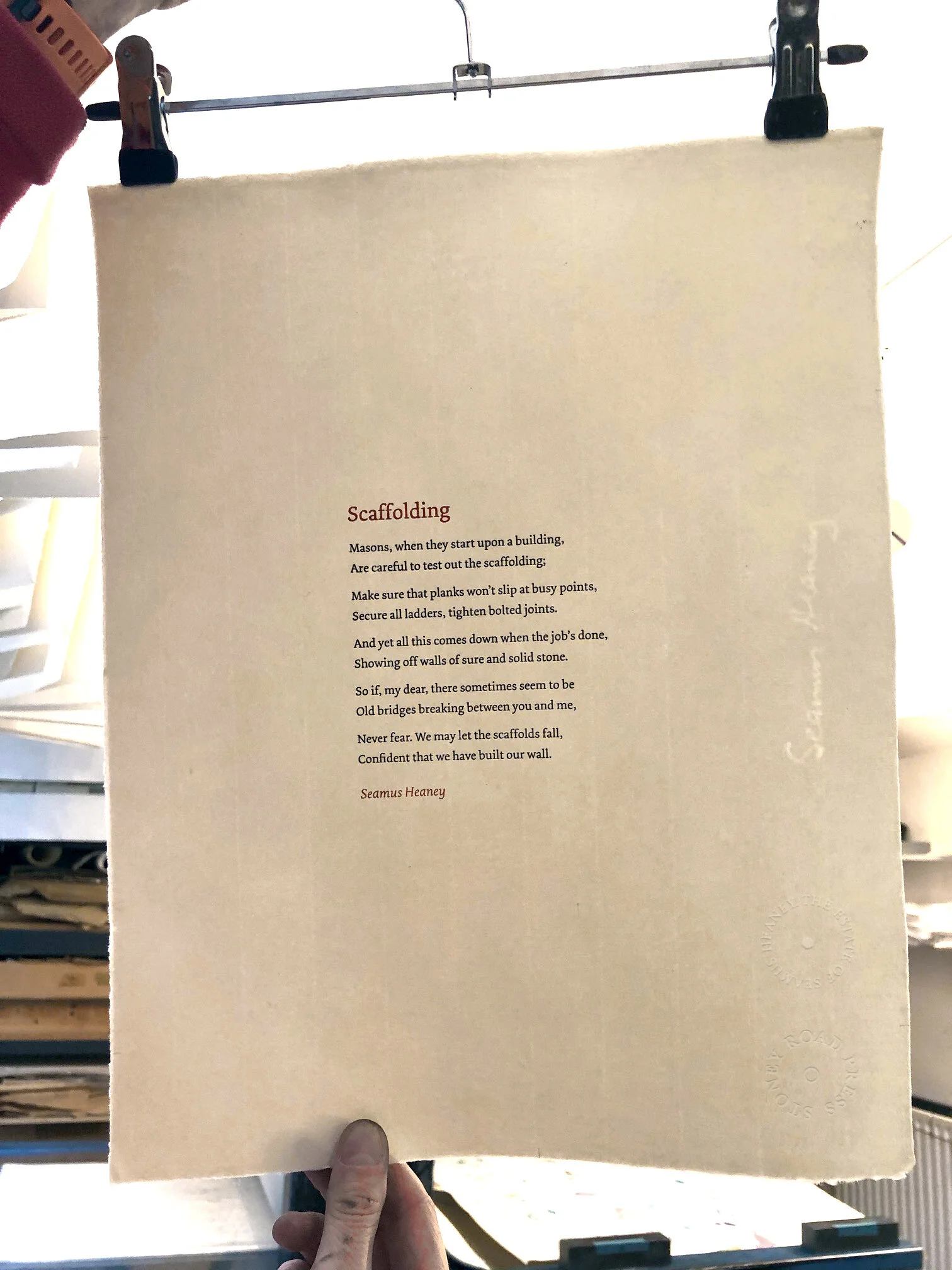

During the several celebratory events, Richard Murdoch presented to guests his Shadowy Waters Press printing of Seamus’s elegy for Ellmann, ‘The Sounds of Rain’, which Seamus read in closing the series; Marie Heaney sang some Irish airs, and the van that transported the lecture party here and there, including members of the selection committee for the next series of lectures (Jon Stallworthy, Barbara Hardy, and Daniel Albright), bravely chauffeured by my co-pit-master Rand Brandes, was full of merriment. In his lectures, and in his full engagement with the occasion, Seamus showed us all how to lift an audience in Ellmanesque language and how to be ‘high on the hog’ and pay tribute to a great scholar at the same time. There were more elevated modes of Southern hospitality – a Dean’s formal dinner for faculty with chamber music – providing a taste of high table with Beethoven and Brahms before we strolled over together for the second lecture like robed Oxford dons. The Friends of the Library hosted a gala reception before the final lecture, after which the ebullient lecture party gathered for nightcaps and fond farewells galore.

Heaney’s inaugural Ellmann Lectures were a major turning point in the history of Emory University, both for the library and the future success of the Ellmann Lectures. When he completed his lectures, he quite spontaneously handed over to the library all the manuscripts, typescripts, and correspondence related to them in Ellmann’s memory. It was a gift of great moment, equal in its packet of pages to the impact of a score of major collections, which followed in its aftermath. It moved and inspired the director of special collections, Dr. Linda Matthews, to say, ‘This is so marvelous and unexpected. Why don’t we continue to build contemporary Irish archives as well as modern?’ It moved the University to commit funds to build a research library of living writers, one that has surpassed our wildest dreams and greatly enhanced our teaching mission, on a scale that Ellmann had called for a decade earlier. Let me call the roll of those contemporary Irish poets and writers whose papers to date have come to the Rose Library as part of the Heaney legacy. The stories associated with each are enough to fill a volume: Michael Longley, Derek Mahon, James Simmons, Seamus Deane, Ciaran Carson, Paul Muldoon, Thomas Kinsella, Peter Fallon and the Gallery Press archive (with its rich collection of Heaney and Friel), Frank Ormsby and the Honest Ulsterman archive, Eamon Grennan, Medbh McGuckian (including the tapes and typescripts of her Conhrá with Nuala Ni Dhomhnaill), Joan McBreen, Rita Ann Higgins, Tom Paulin, Desmond O’Grady, Edna O’Brien, Denis O’Driscoll, and Roy Foster. These are accompanied by the Ted Hughes archive, which contains his letters from Heaney, whose correspondence contains his letters from Hughes. The creative and critical assemblage of what Eamonn Grennan has called an ‘Irish village’ has become not only a primary resource for original, archive-based honors theses, dissertations, essays, books, and editions, but a major repository for author biographies and literary-cultural histories of modern and contemporary Irish literature.

Seamus’s periodic visits to Emory after his Ellmann Lectures led to an invitation to give the Commencement Address and receive an honorary degree in May 2003, conferred by then President William Chace, Seamus’s friend since they met at Berkeley in 1971. When President Chace announced his retirement for September, Seamus returned for a reading in honor of his leadership and achievement. ‘No visit I’ve ever made here has been without great personal significance,’ he said in taking the podium. ‘All in all, Emory has proved itself a home away from home for many writers.’ All in the audience were then stunned by his surprise announcement:

When I was here this Spring for Commencement, I came to the decision that the conclusion of President Chace’s tenure was the moment of truth, and that I should now lodge a substantial portion of my literary archive in Woodruff Library, including the correspondence from many of the poets already represented in Special Collections. So I am pleased to say that these letters are now here and that even as President Chace is departing, as long as my papers stay here, they will be a memorial to the work he has done to extend the University’s resources and strengthen its purpose.

The new materials, which complement previously acquired manuscripts and letters and an extensive collection of his published works, include personal and literary papers, thousands of letters to Heaney covering his entire career, reviews of his works, news clippings, translations, periodicals, tape recordings, photographs, programs, audio-visual and promotional materials.

Meanwhile, the Ellmann Lectures have become one of the most prestigious series in America, the names of Ellmann and Heaney attracting an impressive list of writers and scholars who have been pleased to lecture in their distinguished company, including Salman Rushdie, who gave the Lectures in 2004 and who subsequently placed his papers at Emory, to the surprise of many. I remember him saying at one point in the process, ‘If Emory’s library is good enough for Heaney, it’s good enough for me.’ The biennial Ellmann Lecturers to date have included, in addition to Heaney, Denis Donoghue, Henry Louis Gates, Jr., Helen Vendler, Anthony Burgess (died before delivery), David Lodge, A. S. Byatt, Mario Vargas Llosa, Salman Rushdie, Umberto Eco, Margaret Atwood, Paul Simon, and Colm Tóibín.

For thirty-two years Seamus Heaney’s occasional presence greatly enriched the undergraduate and graduate lives of a thousand or more of Emory students and bestowed great distinction on the Rose Library and the Ellmann Lectures, legacies that have reshaped the character and identity of the humanities at Emory, which became one of his spiritual homes, or havens. Seamus lived life and poetry large and with boundless largesse. Like people everywhere who experienced his presence and art, we also observed his exemplary conduct as a world poet, his constant alertness to the wishes of his hosts and audiences, his selfless conscience and imagination in responding to them with an open hand, leaving his down-to-earth imprint everywhere, leaving us, like the onlookers in Seamus’s ‘Thatcher’, watching him skillfully pin down and stitch a beautiful roof-world out of wheat-straw, ‘gaping at his Midas touch’.

- Professor Ronald Schuchard, April 2018