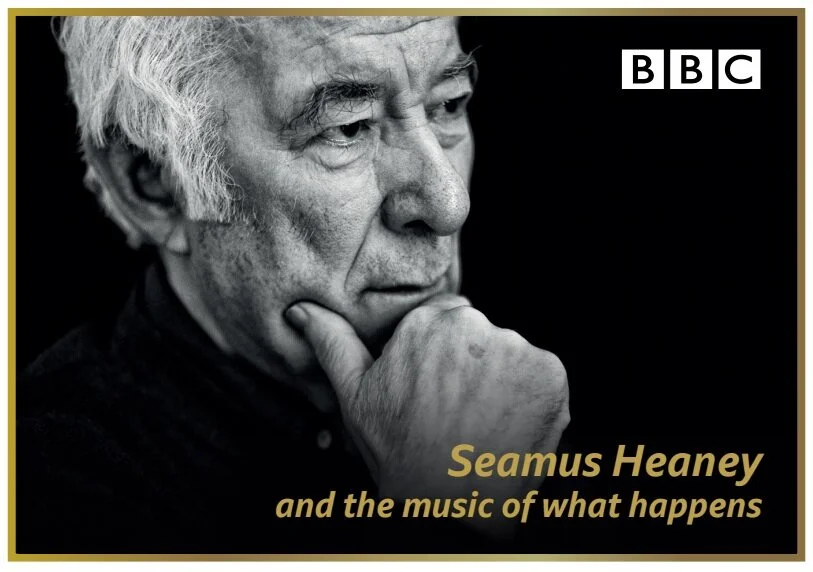

Throughout 2019, the year that would have marked Seamus Heaney’s 80th birthday, poet and translator Marco Sonzogni will celebrate Heaney’s work with a series of pieces based on the sounds in his poetry. Here, he starts at the beginning, with ‘Death of a Naturalist’, the title poem of the first collection.

Every piece in this year-long series will feature a passage from a poem that contains a reference to sound. Seamus Heaney’s poetry is a sound library, a chamber of resonance where reality and imagination come together in unison, so much so that even when he describes silence, he does so in a way that captures and conveys sound, be it emotional or physical - the sounds of inner feelings, or the echo of something in the mind’s memory. And the sweetest sound of all, as Finn MacCool says in an Irish legend, is the music of what happens.

We start with ‘Death of a Naturalist’, lines 1-6 (listen below):

All year the flax-dam festered in the heart

Of the townland; green and heavy headed

Flax had rotted there, weighted down by huge sods.

Daily it sweltered in the punishing sun.

Bubbles gargled delicately, bluebottles

Wove a strong gauze of sound around the smell.

This description is truly tridimensional, completely believable and, above all, frighteningly real. As a child who grew up in a small country village, reading this brought back familiar feelings: the sensation of something known, experienced and learned.

Every Sunday morning before Mass my father would sit my brother and I on either arm of his lizard-green armchair, open a box and flick out in front of us card after illustrated card: animals and plants from around the world, with their Latin and local names, their habitats and their habits, their unique ability to immediately install lasting wonder and fear. So weekend walks through nearby fields and forests were understood as pages in the book of life, eerily energising and emboldening. And safe, for as long as my father went with us, more Pliny than Virgil.

Then time came for me to go alone. And there I was, one afternoon, fast-tracking through a known path into what had to that point remained unknown: a marsh, ring-fenced by wind-swept reeds, now hush now hissing. I went as close as I could go, stopped where the ground beneath me became soft and wet. And there I heard it, the ‘coarse croaking’, and there saw them, the frogs: some green, some brown; some smaller, some bigger — a hoarse parliament of amphibians in full session. Cleverly camouflaged, a senator of that parliament sat still and sleepy in the wings, nonchalant but note-taking.

So when my unpracticed hand got too close for comfort as I tried to part the reeds and take a better look at what was happening with the frogs, something leaped — an arrogant, angry, assertive leap. There it was: a toad. It looked like a blunt-headed, four-legged, wet-wrinkled truffle then. Now, I would liken it more to the tumour they removed from my father’s kidney many years later. I sickened, turned, and ran, as the poem says. I sure did.

Listen to Seamus Heaney reading the rest of ‘Death of a Naturalist’ below, and share with us your favourite sound from the poem, or another poem in the collection, and the memories it evokes, or tweet us @seamusheaneyest.