Professor Iggy McGovern – physicist and poet – sheds light on a phenomenon that finds echoes in one of Seamus Heaney’s best-loved poems

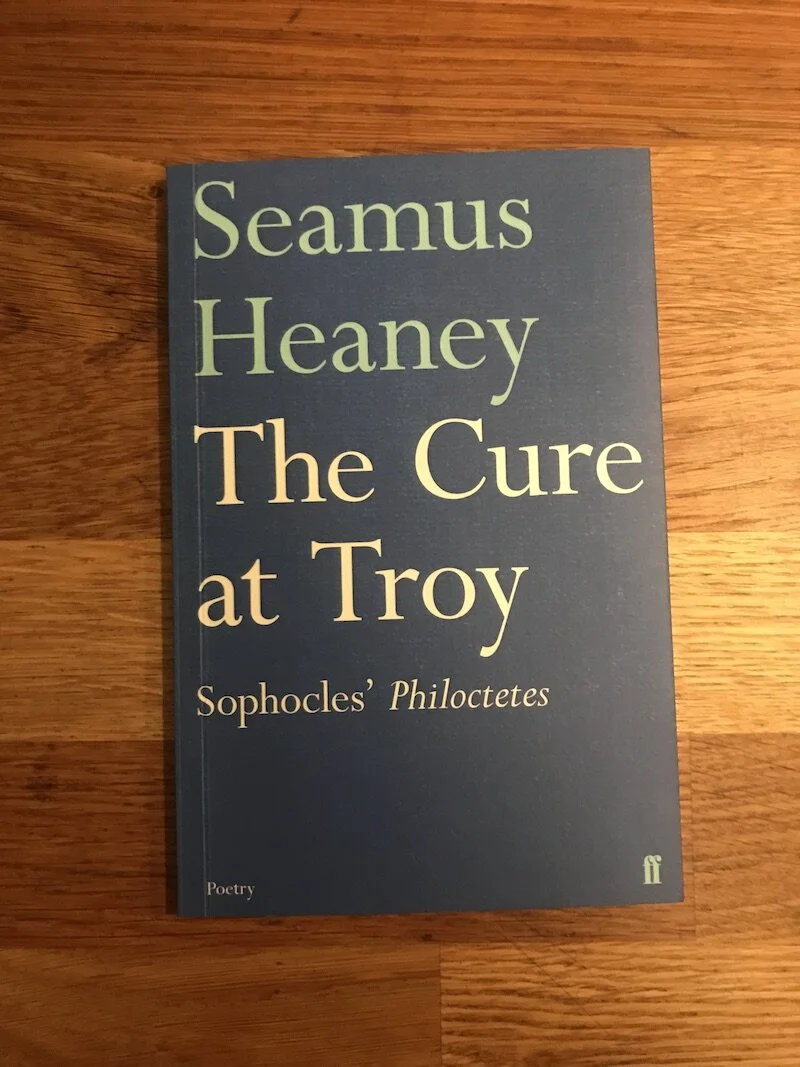

Topping the escalator to Departures at Dublin Airport’s Terminal 2, I make my usual mental genuflection towards the Peter Sís-designed tapestry for Seamus Heaney that hangs high above the security desk; I do this in fond remembrance and with deep gratitude. Two decades ago, the already overburdened Nobel Laureate provided the reference that parachuted me into a Visiting Fellowship (Physics & Poetry) at Oxford’s Magdalen College, and much more besides. Today, I make a long overdue and wholly inadequate attempt to repay the compliment.

I am bound for London’s Tate Britain, to take part in a seminar ‘A Rainbow of Science and Art’. This is one of a series inspired by John Constable’s painting ‘Salisbury Cathedral from the Meadows’, and it focuses on Constable’s later addition of a rainbow in memory of his friend, John Fisher; the rainbow is ‘earthed’ at one end on Fisher’s house. My talk, which is titled ‘Refracting Rhymes’, aims to meld the physics and the poetry of the rainbow and other optical phenomena that arise in the atmosphere.

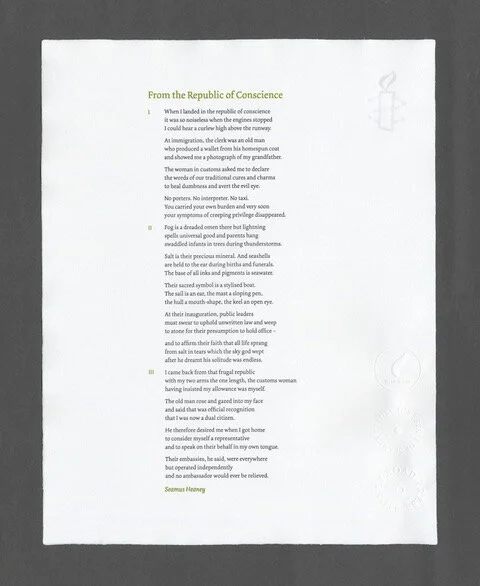

Rainbows arise from the refraction (i.e. bending) and the reflection of light by spherical raindrops; they are celebrated in the poetry of John Milton, John Keats, William Wordsworth, Elizabeth Bishop and many others. In poetry, as in common speech, the term rainbow has been diluted to cover any spectrum of colour and so Bishop confuses refraction and thin film interference in her poem ‘The Fish’; Keats in ‘Lamia’ cautions us against attempts to ‘unweave a rainbow’, seemingly unaware that the rainbow is itself an unweaving of white light! I am on safer ground with the related phenomenon of The Glory, even though it is best viewed from a plane. So called because its halo is centered on the shadow of the observer’s head, it begs some association with Yeats’s ‘An Irish Airman Foresees His Death’.

But my star connection is the ocean mirage. In this case the light is bent in a convex arc – it is the opposite effect to the desert mirage in which the light is bent in a concave arc, such that the weary traveller ‘sees’ an inverted image of a palm tree. But I am both here and there with the ocean mirage, by which the land-based observer ‘sees’ an upright image of a ship in the air – surely the same ship that appears in the little ‘wonder-tale’ of ‘Lightenings viii’, the Seamus Heaney poem that inspired the airborne imagery depicted in the Sís tapestry:

The annals say: when the monks of Clonmacnoise

Were all at prayers inside the oratory

A ship appeared above them in the air.