Seamus Heaney and Geraldine Higgins in Atlanta, 2013.

This summer, the National Library of Ireland’s landmark exhibition, ‘Seamus Heaney: Listen Now Again’ will open at a new cultural space in the Bank of Ireland on College Green. My dream job as curator of this exhibition has been to delve into the amazing literary archive at the NLI, donated by the Heaney family in 2011. Heaney himself loaded the boxes of material into his car, drove to Kildare Street, and carried them into the library that he and so many Irish writers used and loved.

I first met Seamus Heaney when I was a teenager growing up in Ballymena, Co. Antrim, fifteen miles from his home place of Bellaghy, Co. Derry. When his Selected Poems was assigned on the English ‘A level’ syllabus, it was the first time that we had the chance to study a living Irish writer. The exam question was something along the lines of ‘How accurate is it to describe Seamus Heaney as an Irish poet?’ We all scribbled our standard answer that while he was, of course, Irish, the themes addressed in Heaney’s poems were universal and therefore he was in a very real sense an international poet. But as children of the Troubles we knew that he spoke about our lives and in our language in a way that made our experiences knowable and legible to ourselves.

Like many people in Ireland, I became a follower of Heaney, attending readings and lectures in Dublin and later in Oxford and Atlanta. Whenever I was in his orbit, whether in lecture halls, classrooms, restaurants or pubs, he took care to include everybody in the circle of his attention. No one was made to feel unnecessary to the warmth of his welcome.

In 2002, I drove up from Atlanta to Hickory, North Carolina, with my husband, Rob, and our baby daughter, Liadan, to attend a reading and exhibition on Seamus Heaney at Lenoir-Rhyne College. At the party afterwards, I was shown and held for the first time a rainstick, like the one in the poem of the same name dedicated to our friends Rand and Beth Brandes. As I turned it over in my hands, I heard the ‘downpour, sluice-rush, spillage and backwash’ that Heaney describes. It was a sound that I would remember when planning the NLI’s new exhibition on the work of Seamus Heaney.

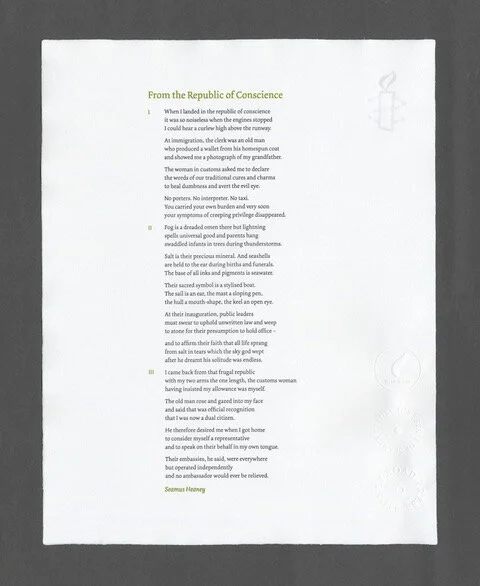

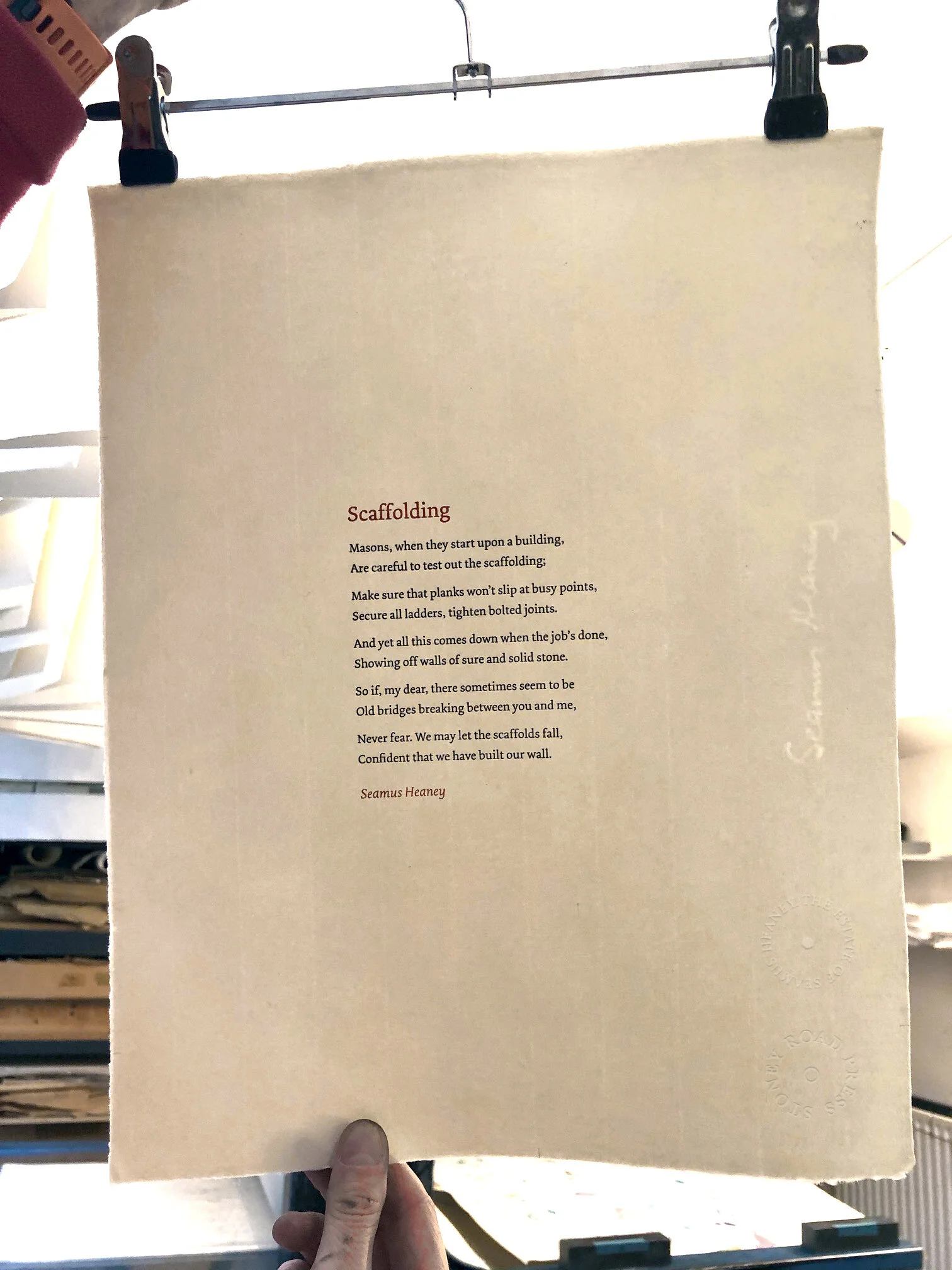

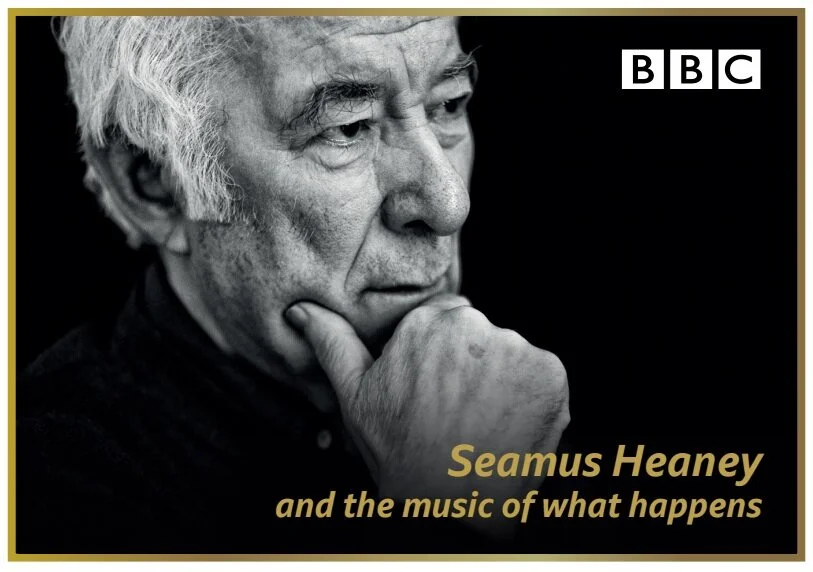

‘Listen Now again’ grew out of an earlier exhibition that I curated at Emory University in 2014 – ‘Seamus Heaney: The Music of what Happens’. Like the Emory exhibition, the NLI show reflects on the importance of listening, not just to the sound of Heaney’s poetry but to a music ‘that you never would have known to listen for’. Heaney’s mission as a poet is not just to capture the music of what happens, but to urge us to pay attention. Indeed, the poem ‘The Rainstick’ describes how something as ordinary as a cactus stick filled with dry grit or grain can be transformed into something miraculous – the sound of rain.

The theme of transformation is the guiding thread of ‘Listen Now Again’, which follows the trajectory of Heaney’s poetry from the earth-bound bog poems of his early work to the airiness and uplift of crediting marvels in his later career. Visitors may at first find themselves in familiar territory with Heaney’s beloved early poems evoking the traditional concerns of his farming family and the everyday miracles of transforming cream into butter, straw into golden thatch. Then, we will move ‘behind the curtain’ examining Heaney’s creative process in order to show how he transforms the ordinary world into extraordinary words.

At the heart of the exhibition are Heaney’s notebooks, some nondescript jotters filled with drafts, to-do lists, and occasional diary entries, others bound and carefully dated. The overall impression is one of graft and craft – recording the hard work of the poet as well as the polishing and refinement of poetic technique. In Stepping Stones, Heaney describes the feeling of starting work in a ‘big hardbacked blue notebook’ not long after returning from his honeymoon:

‘I was like a pilot standing on the edge of an aerodrome, looking out at the plane he would have to fly. There was a terrific sense of having arrived somewhere, and at the same time a definite anxiety. Would you get off the ground again – and on course – and then get landed again safely?’

As we find out, when we examine this big hard-backed blue notebook, Heaney’s flight onward and upward was assured.

In the occasional diary entries, the outside world intrudes on Heaney’s working day with important events like the death of poet Robert Lowell or his election to the poetry professorship at Oxford as well as notes scribbled down in a hurry such as ‘3rd May. Central Garage Bray while VW was being fixed’. Visitors will also glimpse poems composed on the fly such as a draft of ‘Trout’ written on a torn envelope addressed to Heaney at St. Joseph’s training College in 1964. Heaney later describes in a letter the exact moment when ‘Trout’ was scribbled down: ‘I remember exactly how it was written – at one sitting, quickly, in my girlfriend’s flat when she and her cousins were examining new clothes they’d just brought in’.

My favourite notebooks on display are gifts from the Heaney children, described in this diary entry for Christmas 1973:

The boys gave me this – one from Michael and one from Christopher so I am writing in them immediately. It’s half nine, Chris is still in his pyjamas, Christmas Miscellany is on the radio, Marie is making breakfast and Catherine Ann, 8 months old today, is sitting eating her finger with her two bottom teeth saying Ba Ba.

Such moments transport us from our sense of the poet at work to an encounter with the poet at home, full of the joys of being in the present.

My other favourite piece in the exhibition is Heaney’s old desk, on loan from the Heaney family home where it sat under a skylight in the study overlooking Sandymount Strand. Writing about this century-old inheritance from his great-uncle, Heaney describes ‘the grain and grooves’ of the wood ‘worn down by a hundred years of scrubbing’. He ends by describing what this inheritance means to him:

So nowadays when I lift my eyes from my computer screen, lean back and run my hands over the worn contours of those ancient boards, I know I have inherited more than a table. A responsibility has been passed on, to value well made things, but especially those invested with meaning by long human care.

Ultimately, what we find when we turn to Heaney’s notebooks and drafts, letters and printed books is not just the invaluable poetic legacy but the human traces of a writing life unfolding in real time. I have been thinking a lot about time and place as I work on the final pieces for the exhibition. When I teach the poem ‘Follower,’ I often tell my students that it is a poem that will resonate differently for them at various points of their lives. That what strikes them as harshness in the last line ‘But today/ it is my father who keeps stumbling/ Behind me, and will not go away’ will change into something more complicated as they and their own parents age. I know too that they will end up where the poem begins – thinking about the legacy of love.

In fact, when Heaney donated his papers to the library, he invoked the title of what was to be his final volume, Human Chain, ‘It is a privilege and an honour to have my own worksheets, drafts, manuscripts and typescripts in our National Library, joining the great writers of the past and present who have also contributed. It is all part of a written, human chain.’ For me, these words illuminate what curatorship really means – ‘like a cure/you didn’t notice happening’ – to take care of the well-made things we value for the future.