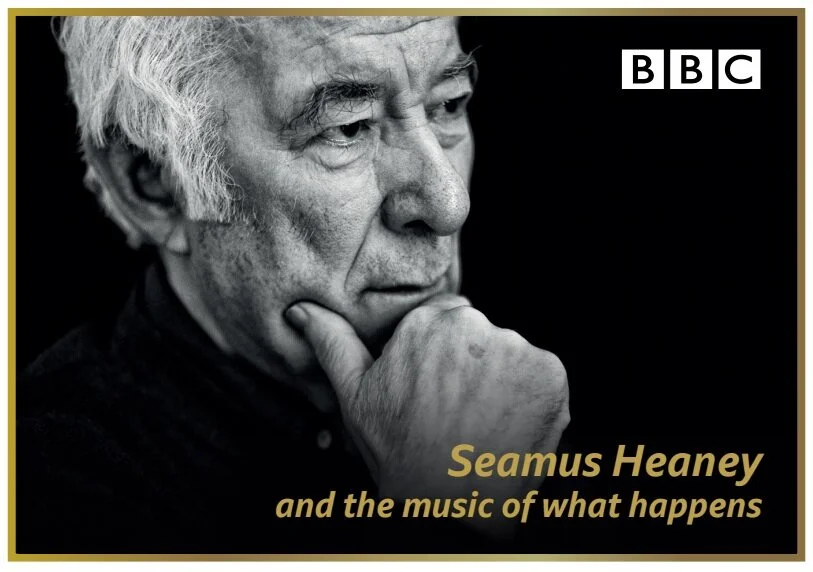

Composer and musician Neil Martin – a long-time friend of Seamus Heaney – has taken the poet’s translation of Sweeney Astray and set it to music for a special St Patrick’s Day concert in Dublin. Here he writes about the challenges and joys of finding the music in the centuries-old story of the mad bird king…

With so many elements funnelled into it, setting Sweeney, or Buile Shuibhne, to music – and specifically writing a macaronic song cycle for solo traditional voice and orchestra – was never going to be a straightforward thing. To begin with, there was the lore and saga and history of a multi-layered story dating back to the 7th century, a story at one level about the outsider; about something of the unsettled (and incapable-of-being-settled) poet tormented in his quest for peace; a story about the tussle of yearning for a truth, via the imaginative versus the restrictive; a story about the changing landscape of Ireland from pre-Christian to Christian – all of these aspects threw up challenges enough. Then there was the matter of thinking in and around and between two languages and two texts – the Irish being that of JG O’Keeffe’s 1913 edition, and the English, Seamus Heaney’s sublime translation from 1983, Sweeney Astray. For me, composing a crotchet was just not possible until I knew what text I was setting, and so began the task of editing Sweeney Astray. (As I write, hearing myself say those last three words makes me quake.)

Generally, singing a sentence takes longer than saying one, so I felt from the outset that in order to tell a version of this epic that retained its flavour and arc, the role of narrator would be essential. Fairly immediately, working now primarily from Heaney’s text, the division of the story-telling between singer and narrator became clear – the singer would sing the quatrain verses of Sweeney and the narrator would narrate the prose, Greek chorus-like. But editing a work of such transcendent artistry, meddling with his words, caused me many’s the sleepless night from last August. That Seamus had been a friend of more than 25 years only added to the weight of responsibility.

Even as I was working solely on the text, however, hooks and bites and bits of melody and harmony were arriving in – the sheer, solid rhythm and hypnotic pulse of the quatrain verse offering up ideas, the cadence of Heaney’s lines, ever-respectful of the Irish, nudging me towards their latent songs. Once into this world, it became all-consuming: day and night, night and day, eating, breathing, living (rarely sleeping) and, at the most difficult times, cursing Sweeney. I wrote a great deal of the piece in the appropriately sylvan surroundings of the Tyrone Guthrie Centre at Annaghmakerrig, in County Monaghan, where on late afternoon walks through the grounds in search of much-needed inspiration, I found myself on more than one occasion addressing an innocent bird as it flitted between trees as “Sweeney”, swearing at it and begging for help in finding elusive notes.

During these trying times, I was comforted in knowing that those performing would bring a whole other dimension to the work, lift it off the page and take it out to an other side. I knew without reservation that the singer, Iarla Ó Lionáird, his own life steeped in Gaelic poetry and song, would, with his unique and beguiling timbre, empower the melodies to soar and caress like few others can even dream about. A life-long admirer of the work, it was Iarla’s suggestion in the first place that I consider setting Sweeney. The narrator, Stephen Rea, a collaborator of three decades, has an incomparable empathy with music – we together made a version of Seamus’s Aeneid Book VI in 2016, essentially a conversation between voice and cello, where once again the pitch and fall of Heaney’s lines made setting them to music seem a most natural thing. (I had charted some of these waters before, as back in 2012 I set part of the chorus of Seamus’s The Cure at Troy for choir and orchestra and so knew something of marrying his generous lines with music.) At various tight corners along the way with Sweeney, I took succour in reminding myself how Seamus often encouraged my own endeavours – lauds after performances, words of reassurance on the phone, over lunch, drinks. You listened to Seamus. You believed his words – they fortified. I remember yet with a crystal clarity that life-changing moment when I first shared a stage with Seamus and Stephen, inter alia, at a Field Day event in the Guildhall in Derry in 1988. My whole perspective shifted after that.

I began working on Sweeney in full earnest in August 2017 and finished the composition at the end of January 2018 – six months of an unpredictable and intense pursuit. Equally challenging and rewarding in extremis, this has also been a warm and spiritual journey, engaging not alone with his otherworldly text but also with something of the essence of Seamus himself – bouncing ideas off him, seeking direction, hoping and praying that he approves of it all. It has been a privilege beyond the wildest dreams.

To the Heaney family, to whom the work is dedicated, for their trust in me, I owe a great deal. I applaud RTÉ for commissioning the piece and thank those at Seamus’s publisher, Faber & Faber for their help. I know under the sure and caring baton of David Brophy, a trusted ally and sounding board of many years, that the musicians of the RTÉ Concert Orchestra will pour their hearts and souls into this on St Patrick’s Day in the National Concert Hall in Dublin. And thinking beyond the now, to get to reimagine a version of a story that has been around for almost 1400 years, and very possibly longer, is a humbling honour that also serves to remind me of how small a grain of sand one is in the grand scheme of things.

Sweeney, a new song cycle based on Seamus Heaney’s Sweeney Astray, composed by Neil Martin, with singer Iarla O Lionáird, narrator Stephen Rea and the RTÉ Concert Orchestra, will take place at the National Concert Hall in Dublin on Saturday 17 March, at 8pm. For booking, please click here.